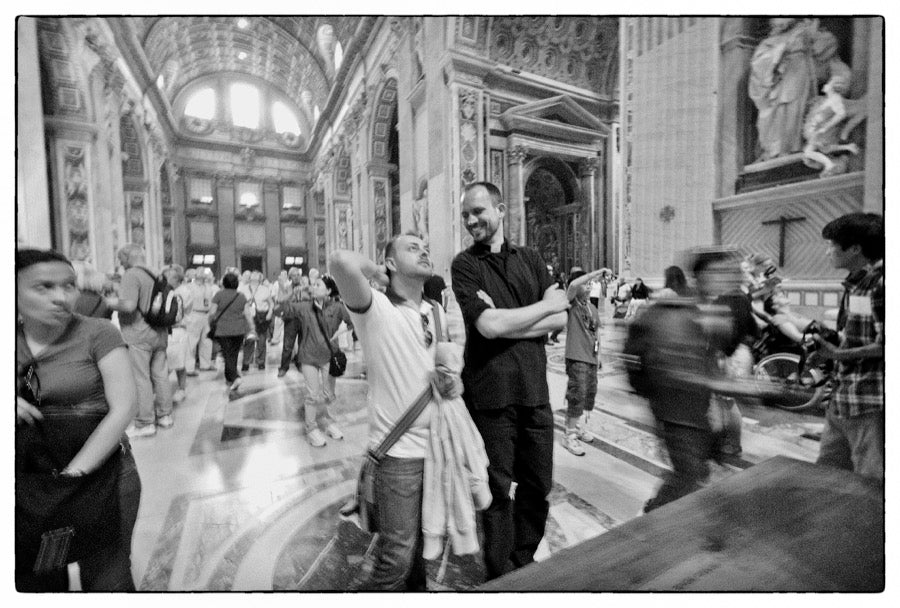

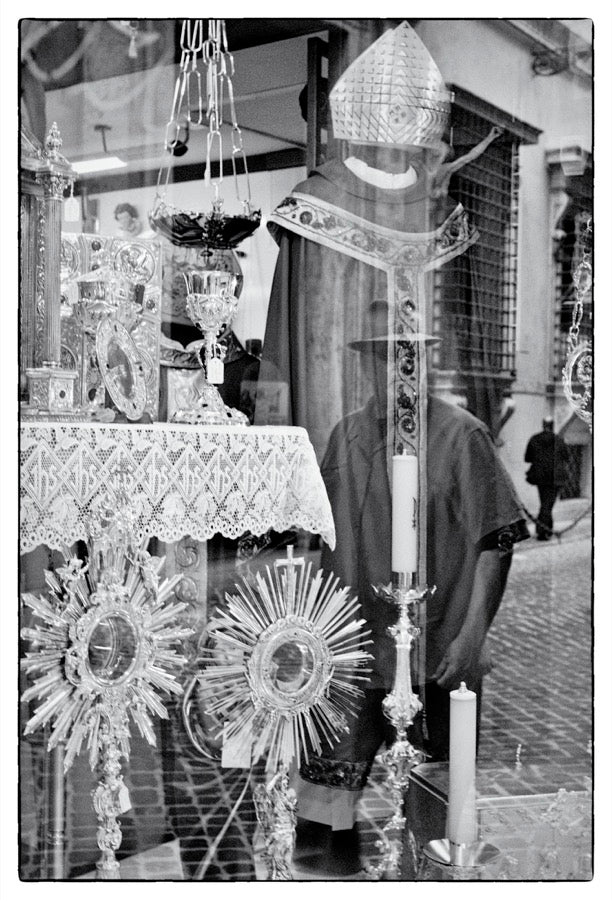

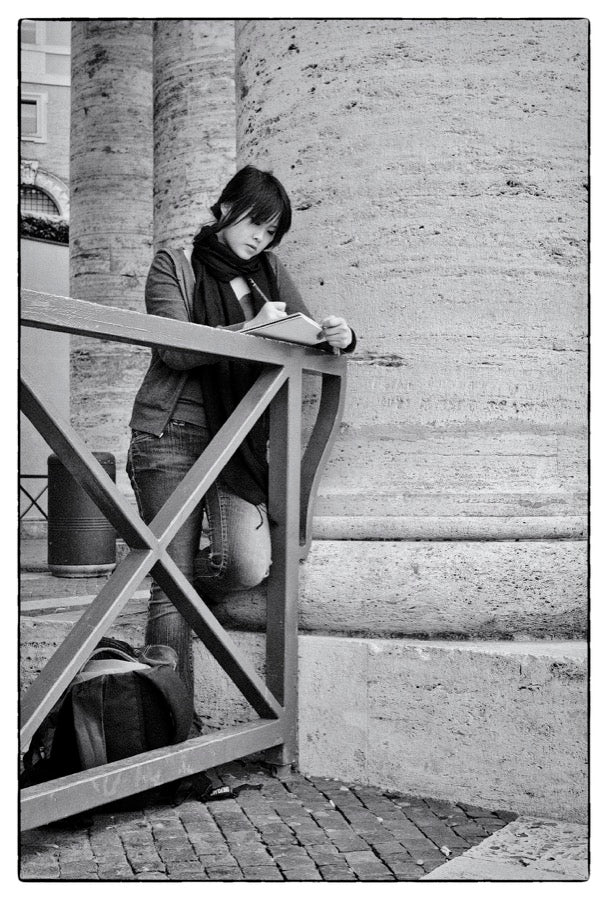

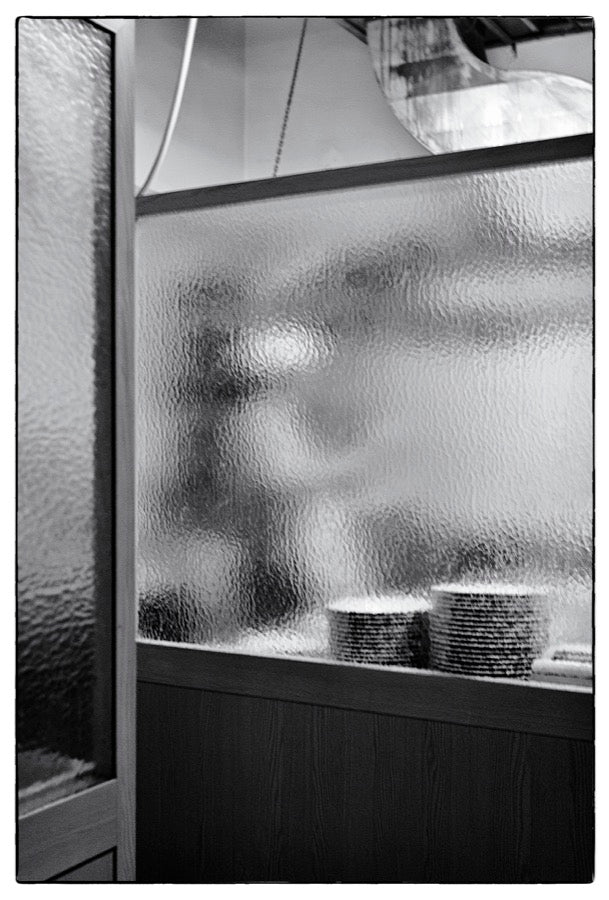

FOUND with Photographer L.P. Pacilio

We met L.P. Pacilio earlier this year when he purchased a few straps for his guitars and cameras. We thanked him and asked about his favorite cameras and which we should consider for our business. He sent us a beautiful response, going into layers of detail on all kinds of cameras and why each one was best for a particular job—he was incredibly helpful. With L.P.'s advice, we bought our first camera and love it. Though, we're still figuring it out.

Through our various email exchanges, we learned that L.P. is a retired photojournalist who cut his teeth in the 60s, travelled the world for work, taught photography at the university level, has exhibited in national and international galleries, and is currently working on a brand new show highlighting five decades of his life's work.

We are thrilled and fortunate to have the chance to ask L.P. some questions on his body of work, tools he prefers, influences, advice for beginners and professionals, and so much more. Please enjoy this month's FOUND interview, it has been our favorite yet. Photographers, this one's for you.

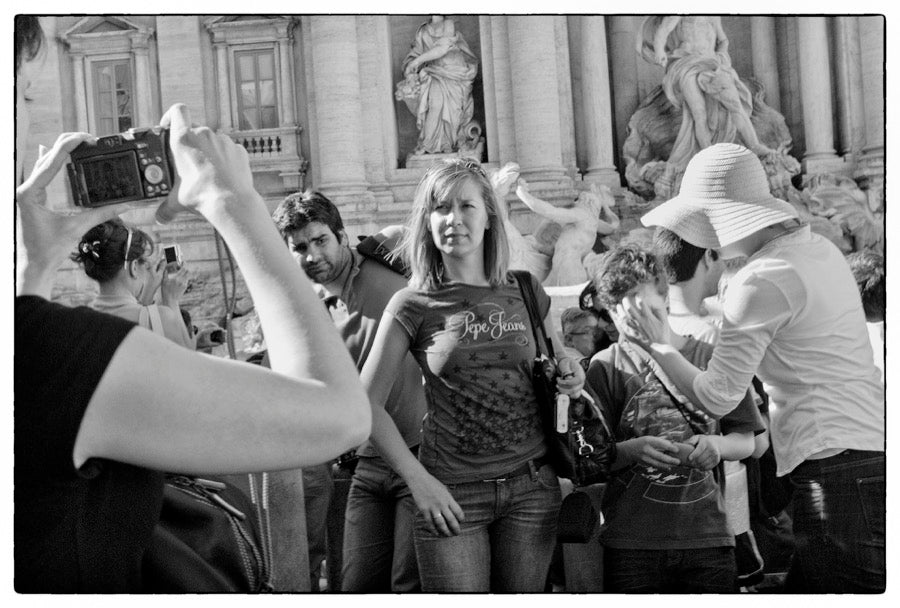

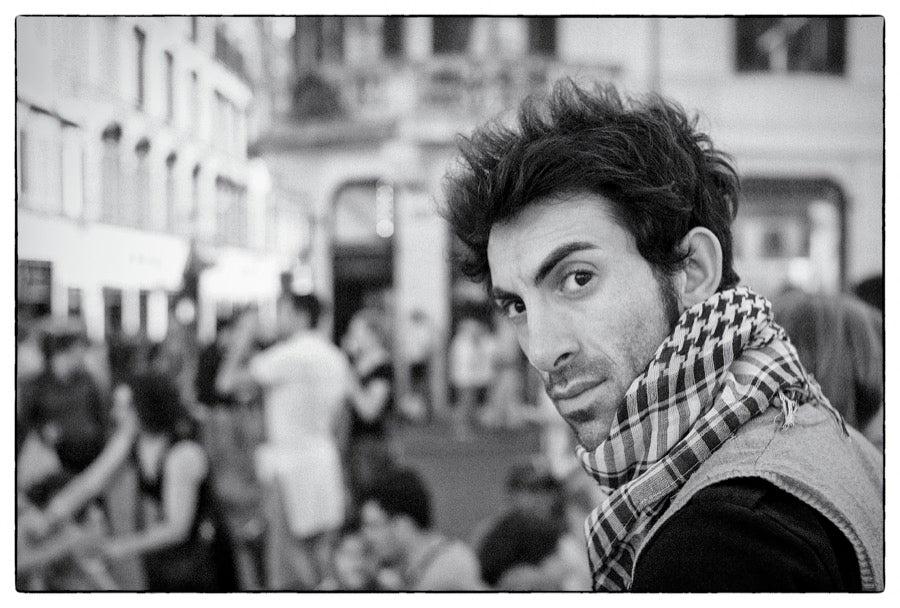

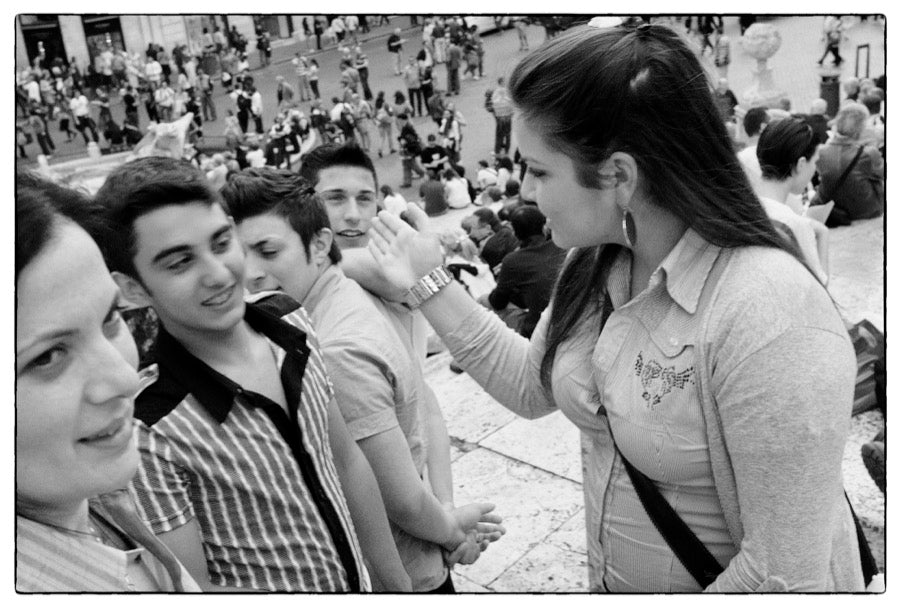

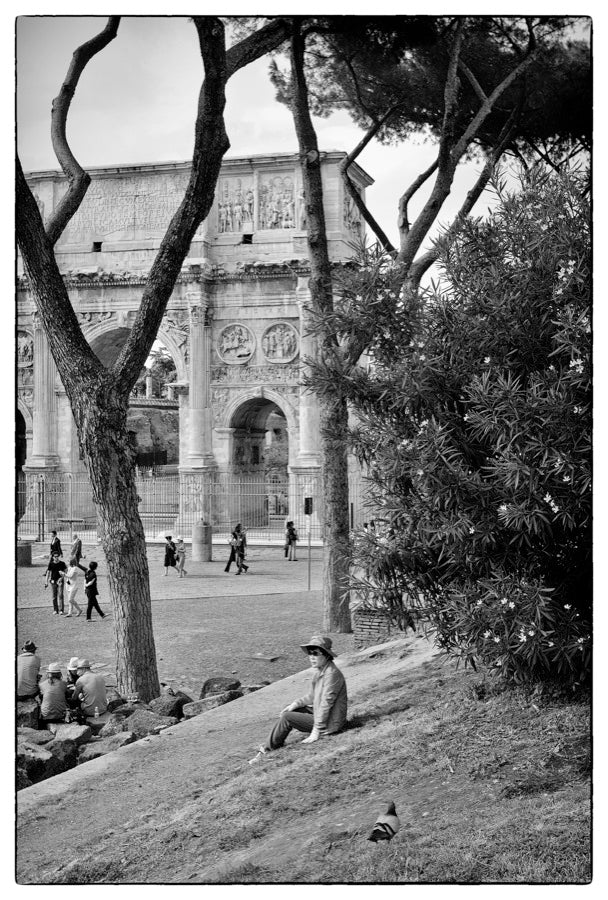

All photos by L.P. Pacilio.

Interview by Liz Earle

Can you take us back to when you became interested in photography?

My journey through photography began as a boy when I purchased a “sun camera” at a local hobby shop. It was a playing-card-sized box with a folding glass cover. The back and sides were printed in a deep green, grainy leather pattern. Under the folding glass cover it was printed with a lens attached to maroon bellows.

The box held a few sheets of printing out paper—photographic paper that required no chemistry, but rather, when exposed to sunlight, turned black except in those areas where the paper had been covered with whatever you chose to place over it. Perhaps it was a coin, some grass clippings, a leaf, or gauze. Those areas of the paper that had been covered were pale grays to whites based on the opacity of the objects.

These images are formally referred to as photograms and several photographers have produced such images over the course of a career, Man Ray perhaps foremost among them. At any rate, to the 10-year-old me it all seemed like so much magic.

The magic persists.

When was the moment you decided to pursue it?

By the time my freshman year of high school had arrived in 1962, I was convinced I was some sort of artist, though completely perplexed as to what my art was to be. I was deeply immersed in Beat literature, had begun playing the guitar, writing lyrics, and had been gifted a Leica IIIf by the father of a friend.

My reading list began with Kerouac then grew to include Ginsburg, DiPrima, Burroughs, Corso, Ferlinghetti, and Snyder. This led me to a fellow traveler of this group of writers, the Swiss born photographer Robert Frank. In his seminal documentary work, The Americans, Frank looked behind the veneer of the almost blind optimism of mid-fifties America and delivered a more unvarnished view of lives led in harsher circumstances than were typically depicted in the wide circulation news magazines of the day. The images themselves were technically rougher, though seen with a well-developed sense of moment and an acute visual elegance. My magical perception of the medium had met the political practice of seeing beyond the superficial.

I was also becoming politically aware and freshly exposed to the work of photographers whose images were communicative not only as documentary journalism, but also as art; photographers like Eugène Atget, August Sander, Walker Evans, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Bruce Davidson, most most especially Henri Cartier-Bresson and his aesthetic of the decisive moment. He wrote, “To me photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a rigorous organization of forms as they are perceived visually.” This thought mirrored the zen musings in the poetry and prose of Gary Snyder and Jack Kerouac. Wide windows on a new landscape began to open and reveal theological, philosophical, and aesthetic paths far afield from the rigid Roman Catholicism of my childhood.

What about shooting photos interests you? Starting out, how did you know that you were good at it?

My most enduring interest relative to the practice of photography has been time—capturing an image that will form within the ebb and flow of life. As quickly as these images form they fall apart. Because of this ephemerality, I find shooting to be something of a transcendent experience, an experience that’s a bit hard for me to describe. I feel as if I am outside of myself. I am more like a radio receiving a signal that an individualized artisan fabricating an image.

When I recognized this condition of transcendence, the near effortless and immediate sense of composition, I knew that if I developed my technical chops to the point of intuitive response, the camera would cease to be a metal and glass intrusion between me and my perception in the moment. As my technical skills grew and with them my ability to respond in the moment, I knew I was a photographer.

Was there ever a moment when you questioned being a photographer?

Trying to make your way in this world as a photographer, or an artist of any sort, is rarely, if ever, a path paved with certainty or security. When I began working professionally in the early 1970s, I found myself shooting with a certain regularity, but living hand-to-mouth. This was discouraging to say the least. I knew little or nothing about business. One small bit of advice I would eagerly offer any young artist is to take a foundational business course. Learn some rudimentary bookkeeping and in doing so come to an understanding of profit and loss. There is no shame in profit. It is the only way to maintain your independence and in doing so persist in the pursuit of one’s art.

In your opinion, what makes a photographer?

Tough question. Photography, perhaps more so than other creative pursuits, requires a mastery of both art and science. Certainly success requires an understanding of compositional issues and the history of the medium, but, additionally, a high degree of technical expertise. If a photographer cannot make expressive prints, be they digital or silver-based, that photographer’s ability to communicate is diminished.

Are there rules to creating the perfect photo? What do you look for in a “good shot?”

There are compositional rules, but, quite frankly, I’ve always been of a mind that every rule is meant to be broken. The Rule of Thirds, the Golden Mean, and the Fibonacci Sequence are compositionally common in a large share of the world’s most recognized art. When I’m on the streets shooting, I don’t give much thought to rules. Experience may have embedded a degree of compositional theory but I prefer to function by intuition. This means I need to accept/learn from failure to a degree equal to my embrace of success.

Tell us about your career as a photojournalist. How did you get started?

I grew up in a small city in Central New York. I wanted out. Given my leftist political leanings and seemingly congenital wanderlust, I soon realized that journalism was my ticket to ride. As a high school student I worked on the student newspaper and yearbook. When it came time to apply for college I had a singular ambition, that being the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. My parents’ ambition for me was a career in medicine. I was strong-willed and resisted their desire.

Any memorable experiences you’d like to share from that time in your life?

I entered university in 1966, a propitious time in American history. I was a staff photographer on the daily student newspaper, The Daily Orange, and covered student protests of the Vietnam War and civil rights movement, as well as protest gatherings in New York and Washington, DC, and the protests/police riots accompanying the Democratic Convention in 1968.

As a working photojournalist I was assigned to multiple situations of conflict and the consequent human migration. These assignments have left me with indelible emotional experiences. Some might call them scars.

What’s the farthest you’ve gone to get the shot?

I have worked extensively on assignment in North Africa, the Middle East, Central America, and South America. These assignments have taken me as far east as Iran and as far south as Chile.

Which cameras do you use and why do you prefer them over others?

Over the decades I’ve used many cameras and camera formats. When you’re working professionally, a camera is simply a tool—a means to an end. Ideally, the camera should not be an intrusion. A camera should be a tool in the way a carpenter would prefer a hammer over a screwdriver if the task at hand was to drive a nail.

As a journalist the Leica was my tool of choice, chosen for the immediacy of its framing, the rapidity and accuracy of focus, and the near silent functioning of its shutter. The Leica is at its best with lenses of wide angle to normal focal lengths. When I needed to turn to telephoto lenses I used Nikons. The use of telephoto lenses was significantly more of an exception than a rule. My modus operandi has been informed by Robert Capa’s dictum, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.”

In the mid 1980s I began photographing architecture and turned to the 4x5 as my primary tool for this specialized subject matter. For me, the Arca Swiss F proved to be the ideal and least intrusive tool for the task at hand.

In recent years, I have come to favor Fujifilm cameras such as the X-Pro and X-E3. These Fujifilm products are quite akin to my Leicas relative to their functionality.

Do you prefer film over digital, or digital over film? Are there times when you enjoy using one over the other?

I no longer care. For me, the hesitance to fully embrace digital was a question of available materials. It wasn’t until around 2005 that digital papers and inks offered both equivalent image quality and longevity (archival quality). It was also around this time that digital sensors offered adequate resolution in order to ensure professional quality image reproduction for typical CMYK offset printing presses.

Why black & white over color photography?

From the start I’ve felt that color can be intrusive. By that I mean that color can too frequently usurp the true subject of an image. While much of my commercial work is in color, over decades the subjects of my personal work have proven to be best expressed in monochrome.

What do you hope a viewer experiences from looking at your photos? Is there a message you consciously transmit?

In a certain very real sense I don’t care if the audience loves or hates a given image or collection of images. I simply want them to have an emotional response. If indifference is the response, I’ve failed in my communicative responsibility.

Who are some photographers that have inspired you over the years, anyone we should know about?

The photographers who initially inspired me are those that still provide inspiration. First among them would be Henri Cartier-Bresson. Robert Frank’s work remains an inspiration as well. Insofar as working contemporaries are concerned, I would recommend looking at the photographs of Josef Koudelka, Trent Parke, and Paolo Pelligrin.

Now that you’re retired, what do you do to express yourself creatively? Are you still actively shooting?

I gave full-time retirement a try two years ago. It didn’t work out. I accept commercial assignments if they interest me and pursue personal projects relentlessly.

What have you learned as a teacher to become a better teacher?

I have taught at the university level for fifteen years. The active practice of photography has been my profession. What I came to understand over my years as a professor was to open my student’s eyes to the simple sensual joy of seeing. Photography needn’t be a professional pursuit. Anyone can revel in the pleasure of a well-prepared meal just as anyone can experience delight in the resonance of sight.

Any advice for those seeking a career in photography? Or for those photographers who are considering putting down their cameras?

The professor in me says get an education. Learn languages so you can navigate the world with some ease. Remain devoted to the work. Find a niche if you want to earn a living—be it fashion, portraiture, architecture, or journalism. Photography, like so many professions, has become specialized. Be prepared for rejection as initially it will arrive with greater frequency than acceptance.

As for those prepared to put their cameras in the closet…if you can’t succeed professionally, shoot for the pure sensual joy of seeing. We are all born with sensual organs. Exploit each of the five senses. Live a joyous life.

What’s next for you? Where can we find more of your work?

I have always been protective of my image, feeling that a degree of anonymity is imperative for me to walk the streets of this world unrecognized. With that said, I have exhibited and published both nationally and internationally. For me the work is its own end. The recognition and acceptance of my work among my peers has provided gratification enough.

I purposely avoid social media preferring to see, touch, taste, and hear via direct experience rather than utilize a disembodied medium.

Following some urging, I am now preparing a retrospective exhibition and possible book which will highlight five decades in the life of an itinerant photographer.

FOUND is a monthly interview series by Original Fuzz Magazine. Our aim is to uncover visual artists from every corner of the world, no matter their background or creative vision. Art is important.

If you like this interview, you'll love the rest of this month's issue. Find it here.

Liz Earle is a writer who likes art. If you'd like to be a featured artist, let her know. Send a message to hello@originalfuzz.com.