On the Road with Eightballs by Tom Feher

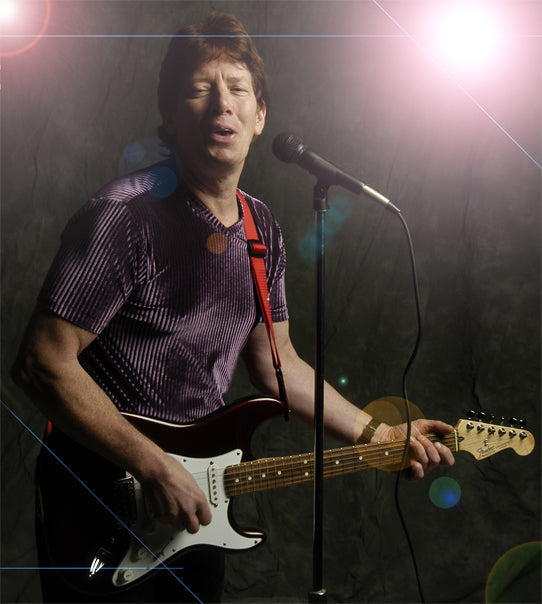

Our guest contributor, musician Tom Feher, is best known for his association with the baroque pop-rock group the Left Banke, contributing as a songwriter and studio musician in the late '60s. Feher cut his teeth on the road in the early '70s, sharing stages with The Turtles, Chuck Berry, Screamin' Jay Hawkins, and others while touring with his band Eightballs, and lived to tell the tale. Below, he recounts the rise and fall, reliving insane moments, and sharing a glimpse of what it's like to be in a real Rock 'N' Roll band.

I got my start in the music industry in 1966 with three co-written songs on the first album by the Left Banke, who had a Top 5 national hit that year with “Walk Away Reneé”. The song has been included in Rolling Stone’s Top 500 songs of all time and covered by one hundred artists or more, including The Four Tops, Linda Ronstadt, Susanna Hoffs, Elliot Smith and Australian singer-songwriter Rick Price.

I got my start in the studio and on the road with the Left Banke, but hit my stride as a unique performer in the early ‘70s as a solo artist and with two bands, Benn Gunn and Eightballs. I did enough living between 1971 and 1975 to fill three books, but for lack of space, I’ll give you the lowdown on Eightballs. My code name for the band,

THE OCTET OF TESTICLES

One night, this is like 1972, I was having a drink at Gerdes’ Folk City in the Village when I came across a musician acquaintance from the Left Banke days, Jeff “Skunk” Baxter. If you’re in the music industry, you probably know who Jeff is. He started out selling guitars from behind the counter at the Dan Armstrong guitar store in New York and he’d always be back there practicing. The next thing I knew he was in a band with some friends of mine, called “Mr. Flood’s Party” who put out an album on Atlantic in the late sixties.

After a while, he kinda disappeared from the scene; but later he began appearing in places, like he was playing with the Doobie Brothers and Steely Dan, and if any of you have seen Blues Brothers 2000 you would have seen him in the Louisiana Gator Boys with Eric Clapton and B.B. King and all those other legendary players. He’s got the big mustache and stuff and wears a beret and plays the blues.

Jeff is now a legend, but at that time he was just a medium-sized legend. I was at Folk City one night sitting at the table, this was back in the days when every other word out of my mouth was, “gimme a Heineken,” and we were drinking our Heinekens and kinda getting a little wobbly and everything and he goes, “What’re ya doin’, Tom?” and I said, “I got a new band, y’ know?”.

And he says, “What’s the name of the band?” and I say, “I don’t know, we just play, y’ know, we just play.” And he goes, “Well, how many in the band, Tom?” and I say, “There’s four in the band.” Jeff says, “Call it Eight BALLS!” I think he was joking, but I took him literally.

I named our group Eightballs to unanimous approval and we eventually adopted the image of the eight ball from pocket billiards as our logo. This gave us a two-pronged attack, because the listener could go with either meaning and be satisfied. I don’t doubt that some people ever got Jeff’s original intention, even though they heard the name Eightballs at scores of concerts.

The original lineup didn’t play many gigs, but there was one memorable show that took place in a venue called Theatre 8 in the City Center complex of West Fifty-Fifth Street. I don’t recall exactly how I knew David Hart, but he was the manager of City Center and also a video engineer / filmmaker of some sort – I think he did experimental things. He had the use of a room which he called Theatre 8 and would promote shows there of various sorts. We played there on a bill with a folk trio called The Braid, a strange combination because they had acoustic guitars and this beautiful three part harmony, and we were cranking out raw Rock ‘N’ Roll. As a rock band, we were unique in two ways, first, we had my Dirty Dozen sex songs which were entirely outrageous at the time; second, we included a good number of country tunes and oldies in our repertoire, something that had not been done much previously in a rock band format.

The original lineup didn’t play many gigs, but there was one memorable show that took place in a venue called Theatre 8 in the City Center complex of West Fifty-Fifth Street. I don’t recall exactly how I knew David Hart, but he was the manager of City Center and also a video engineer / filmmaker of some sort – I think he did experimental things. He had the use of a room which he called Theatre 8 and would promote shows there of various sorts. We played there on a bill with a folk trio called The Braid, a strange combination because they had acoustic guitars and this beautiful three part harmony, and we were cranking out raw Rock ‘N’ Roll. As a rock band, we were unique in two ways, first, we had my Dirty Dozen sex songs which were entirely outrageous at the time; second, we included a good number of country tunes and oldies in our repertoire, something that had not been done much previously in a rock band format.

We were doing Dion’s version of the Drifters’ “Ruby Baby,” Ray Charles’ hit version of Buck Owens’ “Cryin’ Time”, Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me”, and the Drifters’ “On Broadway”, which we’d turned into a musical-theatrics production number. Downtown, I’d met a struggling actor named Van Goldy and we got to talking about joining forces in some way, so we collaborated with this twist to “On Broadway”.

The band would start off by setting up the groove, nice and soft and uncomplicated. Then, with Dave Hart’s help on the subdued lighting, we’d set up a mood with me narrating about being a hick coming to the Big City and winding up on Broadway. Meanwhile, Van Goldy was hidden, laying flat on the stage in front of me under a big piece of burlap, or some other type of cloth. We still hadn’t actually begun the song, but while I’m narrating, he comes up out of the burlap and begins a pantomime to illustrate my story. He’s walking in place, gawking like a country boy might do at the lights and billboards, and making his eyes pop out at imaginary girls while I keep rattling on. Then, finally, the drums kick in, the bright lights go on, and I’m singing the first verse, “They say the neon lights are bright, on Broadway.” It was very effective.

The original Eightballs line-up had a short life-span. There were disputes among the three younger members, primarily myself and the bass player versus the drummer. Our sax player, a very mellow older guy, couldn’t stand the friction and bowed out. It wasn’t long before the drummer, Steve, was also out of the group.

Steve came from a family of twelve kids, most of whom weren’t very bright. We used to joke around and say that the brains of two or three kids had been distributed to a dozen, so that’s what you got. Steve had a younger brother, John, who would walk around the streets at all hours of the day and night shaking his head and talking to himself. The locals called him “John the Bat”. Steve also had a wife. Her actual name was Maureen, but everyone called her “Terry” and they lived in the house where we practiced in the cellar. Terry didn’t like me and Skip, the bass player, and we didn’t like her. She had a flat ass and was the Bitch of all time. We used to nag Steve about being pussy-whipped. And, of course, she nagged Steve about being in a band with us. When she thought the music was too loud or we were too snotty or something, she’d start putting poison in Steve’s ear and he’d come to us apologetically and say something like, “Terry says she can’t sleep when we’re rehearsing. Do you think we could find another place to practice?” It was pathetic. Soon we were on the lookout for another situation.

Another situation came about in the form of a promoter I knew, the manager of my first band (Benn Gunn), Steve Bass. Bass had been promoting concerts in the Tri-State area and taken aboard on his ventures a young drummer from Millburn, New Jersey, named Damian Karch.

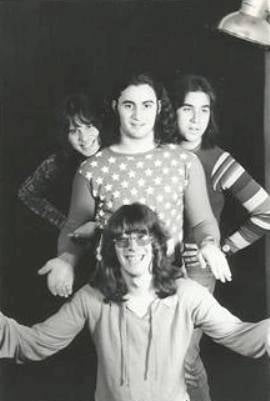

Damian was a slick talker for sure. At the time he wasn’t doing much drumming, I guess, and drumming was his true love if you don’t count money as a main squeeze. Anyway, somehow or another I ran into Bass. And Bass wants to book Eightballs. When he found out we were now short two members, he introduced me formally to Damian who had a great friend in Millburn named Lee Farber, a guitarist. With the addition of these two we had the second and final Eightballs line-up. What you would call the “classic” line-up.

Steve Bass had booked a show at the Bricktown Ice Palace near the Jersey shore, and wanted his protégés to open for two well-promoted bands, Sea Train and Mandrill. Skip, the bass player, and I made daily trips to Millburn to rehearse in the Karch family garage. We rehearsed eight hours a day, five days a week. “Rock and Roll Boot Camp” in Fleischmann’s, NY, where Benn Gunn used to practice, was strained baby food compared to this. It was the real thing, and I became the taskmaster. We had a genuine intention of becoming a super-tight band, a force to reckon with in the world of rock music, and we got damn close. Meanwhile, the combination was an odd one, split down the middle by our respective backgrounds.

There was me and Skip, streetwise and R-rated, in combination with Damian and Lee who’d grown up rather comfortably in a small town in central New Jersey. Damian had an unusual diet, for breakfast he’d eat Captain Crunch cereal in a bowl of Coca-Cola. They had a kind of corny sense of college humor, especially Lee, that was lost on me and Skip. Our idea of funny was to stick your ass out of a moving car and moon the other drivers on the State Thruway. Skip had moved to Weehawken, and his new girlfriend, Janet, wasn’t above flapping her boobs out in public, either.

Lee Farber, born into a comfortable middle-class environment in Queens, New York, had grown up in the Millburn/ Short Hills area of New Jersey, one of the top income earning areas in the nation. For the young people of Millburn, rock music was not an urgent way of life, but more of a “cool thing to do” that could be easily financed by Mom and Dad.

Lee Farber took his musical inspiration from the Beatles, Cream, Hendrix and Zappa. He met Damian Karch at school and in Eighth Grade they put together a short-lived pop-rock band called The Invaders playing material like, “Time Won’t Let Me” (#5 for The Outsiders in 1966). Farber has described Steve Bass as an, “aluminum siding salesman,” through whom he became aware of Skip and myself.

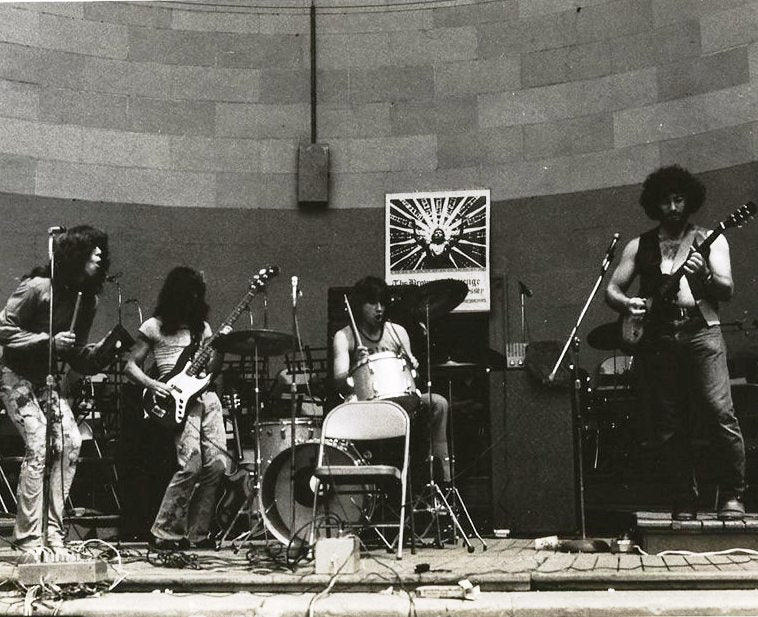

Somehow, we merged the elements into a tight unit that survived for two and a half years doing weekly gigs in Jersey bars, high schools, ball fields and frat houses, and in campy places around Manhattan. Our first gig was probably the one at the Ocean Ice Palace in Bricktown near the Jersey shore. It came off pretty well, all things considered. Our “fan club” from Weehawken came down to applaud and heckle and filled up the front of the audience with more noise than we could muster from our amplifiers.

So, at least, we had a cheering section. We did the set that we’d been rehearsing every weekday for two months, and from the old recordings that still exist, I can tell you the instruments were tight but the vocals left something to be desired. I might have been ninety percent on pitch-wise, but that’s ten percent too little when you want to play in the big leagues. Damian sang like a chipmunk and Lee had what we called the “dying whale” sound. We had a blast, though, playing for a real live audience after all that time in the Karch’s one car garage.

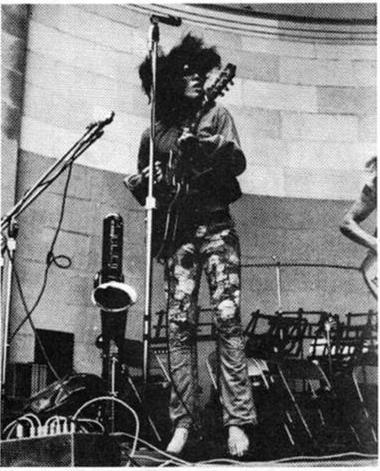

At one point, I heard Lee make an announcement to the audience, “psychedelic cookery” he says. I look over and he’s got a pair of shiny, red silk gym shorts on his head, supposed to be a chef’s hat. He did silly things like that, but you forgave him because he was one of the hottest guitar players around. He could easily go up against Alvin Lee from Ten Years After.

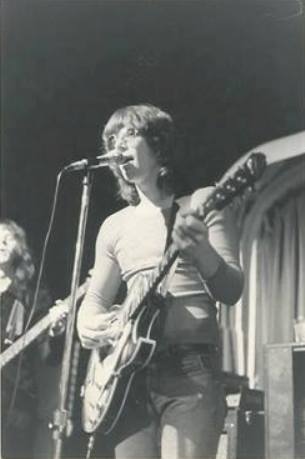

Eightballs was more than just a rock band. We methodically fashioned our performances into a visual event. In my silver boots, I would kick my leg high in the air, Rockettes’ style during Lee’s guitar solos. Skip wore glitter shirts and platform shoes, and while playing his kit, Damian could whistle loud enough to be heard over the entire band.

Lee Farber had been successful in college wrestling, and I’d spent eight years training and competing as a gymnast. On certain outdoor gigs we would do dive rolls over my Wurlitzer electric piano, crossing from opposite sides of the stage, while the bass and drums thundered out a rock tattoo.

During 1972 and ’73, band members in the new incarnation of Eightballs booked ourselves, transported and set up our own equipment, promoted ourselves, and did our own banking and issuing of pay. Because Lee had many friends in various colleges, himself having only recently emerged from the college scene, many of our gigs were played for college fraternities.

I think the first college frat house we played was one down at Stevens Tech in Hoboken near Castle Point, overlooking the Hudson River. I don’t know how we got that one. The pay was minimal, something like a hundred fifty bucks, and the only things I remember about the gig itself was singing “You’re Cheatin’ Heart” as a request, and a keg of beer rolling from the second floor down a long flight of steps and bouncing on the floor.

I’ll share just a few highlights from the college gigs, they were outrageous. There was one in Bloomfield University, which I think we did with a band called Cotton Mather – real punks. At the same gig, a couple of violent women showed up and demonstrated their disgust at my song “Hey! Red (Gimme Head)” by pouring beer on our mixing board and shorting out the sound.

Then, at the end of the gig, the little pricks from Cotton Mather tried to steal our Voice of the Theatre type speaker cabinets, custom-made by Lee. Just think how stupid they had to be, to try and rip off something as big as those boxes. We had a roadie at that time, John Crawford, a wild guy with glasses and hair down to his ass, but he was tough. He almost bit someone’s ear off one time in a fight at one of our gigs. Well this time, he spotted the speakers in the back of a pickup that belonged to one of Cotton Mather’s people. He ran around the front of that car before they had a chance to start it up, opened the hood and ripped out as many spark plugs as he could grab. That was the same gig at which some really drunk member of the audience walked in front of a moving vehicle and went flying through the air to land on top of a grassy knoll. That dude was so drunk he didn’t even feel it! Got up, looked around in confused annoyance, and walked away.

I think my favorite and most memorable college gig was at Princeton U. In the first place, it was Princeton! Here I was, a graduate of University of the Streets, bad-mouthed Bad Boy who’d given the finger to all greater established institutions, and one of the frat boys is pointing to a red brick building and says, “…and that was Einstein’s dorm,” priceless!

But that frat party was the bomb. The school had won a football game, and they were set to blow the roof off the ivy covered halls. My first clue was seeing a couple of big beefy football players walking around in dresses and falsies, one with a blue wig and one with a pink wig, with high heels and lipstick. It was a carnival.

During our set, I was concentrating on my guitar because I had just one lead part, in “Born to Be Wild” and I didn’t wanna screw it up. Lead guitar was not my strong suit. So, I’ve got my head bent down and am looking at my carefully placed fingers when Skip starts yelling and digging the head of his bass into my shoulder.

I get the riff done and I look up and Skip is pointing with his bass to the other side of the room, which was something like a banquet hall. Some wild character had apparently wrapped gauze around his head, squirted on some lighter fluid and lit the damn thing up. He was swinging across the room, hanging onto a chandelier, his head aflame. You have to admit that Alice Cooper and Ozzie Osborne could learn a trick or two from the boys at Princeton, maybe they did.

The group was involved in a number of campy outings in the two-and-a-half years of its existence. Among them was a Halloween gig with Elephant’s Memory and John Zacherle in the Grand Ballroom of the New Yorker Hotel on West Thirty-Fourth Street. I’m a bit hazy on the hotel’s name, but I swear to the location, so the New Yorker seems probable.

Steve Bass had gotten together with a North Jersey fellow, John “Jed” DeFillipis, who’d been entertaining thoughts of being a big time rock concert promoter. DeFillipis had been involved in one or two projects with Joe Marra, the owner of the legendary Greenwich Village club, Night Owl. Somehow, Bass, through the Weehawken connection, had gotten a hold of Jed’s ear and persuaded him to join up with him in a venture that would include Damian Karch as a third partner. The trio called themselves “Whipsnade (Bass), Bizonet (Karch) and LeFong (DeFillipis).” The names were no doubt inspired by Groucho Marx characters, as Bass had already promoted concerts under the name “Wolf J. Flywheel,” a Groucho character from the film The Big Store.

Damian had no problem playing both sides of the fence, taking a cut of the promoter’s share and also playing in the band. His main concern was how much money he could make, and he had a Flamenco dancer girlfriend, an older woman from Spain that would pinch his testicles if he didn’t “bring home the bacon”. The rest of us were devoted only to the band and I resented him for double-dealing like that. Whatever the case, the Halloween gig with John Zacherle was a cool gig. After all, Zacherle was the “Cool Ghoul”, and we made a few bucks.

I already knew Zacherle. I’d seen him on television in the late ‘50s when he was hosting Shock Theater, running old horror films and talking to his “wife”, a vampire we never actually saw, who supposedly reclined in a coffin while he muttered at her. At the time of our gig, Zach was a radio DJ on WPLJ. Bass set up a meeting with Damian, Zacherle, and myself in the commissary at CBS and we went over the plans for his appearance. We would do our regular set, which included some pretty spooky stuff anyway, and then announce Zach as a special guest. Zach would come out and do two songs, his own “Dinner with Drac” and the Halloween mega-hit “Monster Mash.”

“Dinner with Drac” is a limerick put to music. Zach had the lyrics on big pieces of oak tag, which he would read and then throw to the floor of the stage. I immediately fell in love with it. It wasn’t until years later that I found out he’d taken it to number six on the Billboard charts in 1958. I was hooked from verse one

A dinner was served for three

At Dracula’s house by the sea

The hors d’oeuvres were fine

But I choked on my wine

When I learned that the main course was me!

Zacherle wasn’t the only ghoul we shared the stage with. At a little college up in Connecticut we did a show in which we doubled as the backup band for Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. We met him backstage before the gig and he went over his set requirements with us. Most of the list was just the usual three-chord, twelve-bar blues stuff in various keys. One song called, “Ashes” was just a C chord to an A-minor chord, over and over. Jay’s big theatrical opening number, of course, was his legendary “I Put A Spell On You” which, by this time (early ‘70s) had been covered by Creedence Clearwater and become fairly well-known outside the chitlin circuit.

As the curtains parted, Jay was on a dark stage lying in a coffin, and there were candles lit for an eerie effect. When the music started, he rose up out of the coffin and did his thing. It fell right in line with Eightballs’ outrageous sense of theatre.

Also among our campy gigs was a performance at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. I don’t recall exactly how we got the gig, one connection leads to another and things come up, y’ know? Anyway, we arrive at the museum and we’re given an empty gallery as a changing room.

The curator guy, or whatever he was, tells us we can change there, but under no circumstances touch the valuable painting behind the drape on one wall. It was supposed to be worth around fifty thousand dollars. He leaves us there and we’re changing and, of course, our curiosity gets the better of us. We want to know what kind of painting can be worth fifty grand. So we peek behind the curtain and all we see is a blank canvas.

I’m going, “This guy is pulling our leg. There’s no painting back here. He just wanted to fuck with our minds.” But Damian, I think it was Damian, keeps looking over the canvas and suddenly he calls out, “Hey, look at this!” So we go and look, and up in the corner of the canvas, which was about six feet high and ten feet wide, this huge canvas, up in the top right-hand corner there are four or five stripes of color between three to six inches long. I’m thinking, “No, this can’t be real,” and we’re debating on whether anyone would really pay fifty grand for something like that and finally agreed that it was not only possible, but very likely in the kind of company that hung around art museums.

Meanwhile, the equipment is set up and we go out into the reception room where the snooty rich of New York City are daintily holding their champagne flutes and jingling their jewels and talking through their noses and whatnot. Some genius had worked it out to put us on a bill with Odetta, of all people.

Odetta (R.I.P.) was an Alabama native who was referred to by Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. as the Queen of American Folk Music. She was a vocalist, actress, guitarist and songwriter and was also dubbed “The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement” in respect of her work in the cause of human rights. Her repertoire of folk songs, folk blues, jazz and spirituals was far from being compatible with our brash, high volume rock.

We appreciated Odetta as an artist, but strategically it was a nutty combination, putting us in front of the same audience as a sensitive folk artist. And the proof of the pudding was in the tasting.

The hoity-toity audience stopped their chatter, listened and politely clapped for Odetta, but when we started up our own set, they turned around and began talking to each other. I said, “Fuck these assholes, if that’s the way they wanna be,” called a huddle, and we played the rest of the set with our backs to the audience and our faces to the wall. If they can’t take a joke.

Eightballs was also involved in one of the remarkable events in the early 1970s New York City cultural environment, the emergence of the Mercer Arts Center. The Mercer was located in the Broadway Central Hotel, which had opened as the Grand Central Hotel at 673 Broadway near Bond Street in 1870. The Broadway Central had already made its way into musical history when Bill Haley and the Comets rocked the house in the 1950’s. But in the early 1970s the Mercer Arts Center on the Mercer Street side of the huge hotel became a haven for artists of all varieties and even helped lay the foundations for what was to become the punk rock movement.

As I understand it, the Mercer wasn’t specifically designed to be a music venue – far from it. Apparently it was mainly intended as a home for off-Broadway theatre. Somewhat ironic when one considers it was located in the Broadway Central hotel. A comedy called “El Grande De Coca Cola” played there to capacity crowds, and an adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest ran for almost a thousand performances before it was cut short by the collapse of the hotel.

Being so suited for theatre, the Mercer Arts Center naturally brought in some of the more avant-garde forms of music that had been surfacing in the wake of the Velvet Underground. Among the locals that played there were the New York Dolls, New York Central, Teenage Lust, and the Magic Tramps featuring Warhol alumni Eric Emerson.

My friend Tom Finn, bass player and founder of the Left Banke, said in an interview,“I went with Marc Aaron to see Feher play with his band Eightballs at Mercer Arts. I clearly recall Tom up on stage wowing the crowd. Marc and I were impressed. I’m afraid I don’t remember too much else about the Mercer Arts Center, except seeing Patti Smith playing there. Patti was caterwauling a song called ‘They Never Called Pablo Picasso an Asshole.’ I remember saying to Marc, ‘What the fuck is happening? This is not music.’ I couldn’t understand why people would want to hear this type of music.”

There were other more respectable acts there during the short history of the Mercer. I saw Billy Crystal and Orleans in a cabaret style room there; Tom Petty played there too, and Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers. But the New York Dolls made their reputation at the Mercer Arts Center.

Eightballs and the New York Dolls were at odds from the very beginning. The Dolls’ lead singer, if you want to call him a singer, was a Bleeker Street barfly named David Johansson. He was one of those guys whose lips are big enough to make him a Mick Jagger look-alike. Other than that, there was no comparison. David couldn’t sing two notes in a row in tune; hell, he couldn’t sing one note in tune.

And, suddenly, he’s up there on the stage posing and yelling into the microphone and strutting around like a rock star. Really, this is the point where music became a pose rather than a profession. Up until that time it was expected that a musician actually knew something about music.

These guys didn’t give a fuck about the quality of sound, all they wanted was the notoriety and the sex that went along with it. Now, I didn’t mind either the sex or the notoriety, but I like to have mine on a foundation of actual musical skill. My background was with the Left Banke, and the Dolls were a joke to me. Although we later played a few club gigs with them, the first time I actually heard them was at the Mercer.

Their throne room was a theatre up near the front of the place. It wasn’t a particularly large room, and they were playing at an ear-splitting level that was intolerable for even a hard core rocker like me. I think they were playing Bo Diddley’s “Pills.” I could just hear Bo going, “Who are these fruity little clowns? What hole did they crawl out of?” I left after one and a half songs.

Meanwhile, Eightballs got to play way in the back in the Oscar Wilde Room where we shared the bill with Teenage Lust and Patti Smith. Patti opened up the show reading poetry, holding a bird in a cage and occasionally plunking on a toy piano. The group Teenage Lust acquired some fame when their guitarist/vocalist Billy Joe White, formerly with David Peel and the Lower East Side, reportedly took a shit on stage. Now that’s theater for you! Not to be outdone, Skip’s girlfriend, Janet, jumped up on stage during an Eightballs number, “Obscene Call,” zipped down Skip’s fly and proceeded to deliver a serving of fellatio while he never missed a beat on his bass. You could say those were the good ol’ days.

Also playing in the Oscar Wilde Room was my old compadre Jerry Hawkins, from Benn Gunn, who had a band with him on guitar and Jerry Nolan on drums – quite a sound for two instruments and one voice (they added more players later). Nolan was a pretty good drummer who got recruited by the Dolls when their original beat-master, Billy Murcia, went for an extended underwater swim. I think most of these characters are long gone by now. But Jerry Hawkins, “The Hawk” , is still much alive and kicking (ass). Jerry told me,

I remember Mercer Arts Center well, with the like Clockwork Orange décor. When I was playin’ there with KICKS – that fucked up band I had with Jerry Nolan, Billy-fuckin-homo Squires, drunken Danny Sicardi on bass and Junkie Jer ‘the Hawk’ on guitar. Nolan looks at me one day, shortly after his twenty-eighth birthday, and says to me, ‘Well Jer, I think I got about ten good years left in me. So I’m gonna join the New York Dolls and shoot dope, play and die.’ He actually squeezed an extra two years in, I think, before the virus got him.

One night I was playin’ in the Oscar Wilde Room, just me and Nolan, and David Peel shows up with John Lennon who looked like he was trashed on heroin which was probably the only reason he was hangin’ out with David Peel or sittin’ through one of my sets. The limey was there to keep him company. You remember her famous circus act that came to a near final curtain call???

The “limey” was a British girl named Janice who had been the girlfriend of Benn Gunn drummer David Paul “The Whip” Wesley and had now shifted over to servicing Hawkins. The circus act he refers to was an incident in which she jumped out of a third story window and barely lived to tell the tale.

The Mercer Arts Center was unique and it’s too bad it didn’t survive the big structural catastrophe. The catastrophe I refer to was the collapse of the Broadway Central Hotel on August 3rd, 1973. The collapse of the building and subsequent failure of the city to support renovation effectively put the Mercer Arts Center out of business. Seymour Kaback, the air-conditioning engineer who’d conceived and managed the Mercer, deplored the situation as a lack of city pride in its heritage. According to Kaback, the Broadway Central and its theaters were the victims of sublime indifference to our heritage, neglecting our best architecture as we neglect the theater arts.

The Mercer Arts Center was unique and it’s too bad it didn’t survive the big structural catastrophe. The catastrophe I refer to was the collapse of the Broadway Central Hotel on August 3rd, 1973. The collapse of the building and subsequent failure of the city to support renovation effectively put the Mercer Arts Center out of business. Seymour Kaback, the air-conditioning engineer who’d conceived and managed the Mercer, deplored the situation as a lack of city pride in its heritage. According to Kaback, the Broadway Central and its theaters were the victims of sublime indifference to our heritage, neglecting our best architecture as we neglect the theater arts.

For Eightballs, the show continued in various bars, clubs and outdoor venues too. We played in sports fields, and in the Central Park and Lincoln Center band shells. But I’m proud to say we never played CBGB’s. To us, that was slumming at its lowest level. I particularly remember our Lincoln Center gig because I was deathly sick that day. I’d never missed a booked gig, but I was in danger of missing that one because I’d been laid up with the flu in my cramped apartment in Weehawken Heights and I didn’t want to go out or even move my little finger. I was miserable and I told the guys by phone to play the gig without me.

Well, they weren’t gonna go for that, especially since I was responsible for about ninety-eight percent of the vocals. So I’m lying there wishing to die when the doorbell rings and Damian Karch comes in to drag me off to Damrosch Park in his little puke green Datsun pickup. I lay there in the bed of the truck down through the Lincoln Tunnel and up the city streets, wheezing and moaning until we got to the band shell upon which I pulled myself together and did my thing.

We’re in the early measures of a really neat and nasty song called, “That’s The Way I Like Her,” and some smart asses in the audience start throwing things, mostly rotten food. I got hit by at least one egg in that barrage, the big payoff for climbing out of bed sick as a dog to make it, like what? I think it was a freebie.

Another gig at the Central Park band shell, we debuted our new finale number, which was something of a further development of the early Eightballs when Van Goldy came up from under the tarp during “On Broadway.” In this case, we had a large number of inflated eightball beach balls which we’d found through a novelty company, and it was the beach balls that we had hidden under the tarp. Our big final number was “Music’s Gonna Save the World,” which had a long repetitive ending something like the Stones’ “Tumbling Dice.”

When we got to that part, I’d invite the audience to clap along, and suddenly the balls would be released from under the tarp and go rolling out into the audience. It was really cool, if only we could have perfected it and made enough money as a band to afford buying more and more beach balls.

We also had the great idea of buying boxes of women’s panties in three sizes and having them imprinted with the Eightballs logo. We would set them out on the front of the stage and let the girls in the audience fight over them. It was just wishful thinking, but crafty, ever so crafty!

Eightballs played a number of places with the Dolls, at My Father’s Place in Roslyn, Long Island, and one in a little dive on Queens Boulevard where I received an extended education in the music business from, of all people, Arthur Kane, the Dolls’ bass player.

The gig had been set up for us by my old enemy Steve Bass (The Bass Hole), who booked it for two hundred dollars and gave the band fifty percent, or one hundred, which split four ways gave us twenty-five bucks a piece. There was a pitiful band on stage called Rags, so Skip and I went out in front of the club to take in a bit of night air, and that’s where we were when Arthur came out and joined us. The Dolls had their album out and were getting lots of publicity.; we figured that at this point they had it made.

So Skip and I are grousing about the Bass Hole saying, “Can you believe it? He takes half the money and all we get is twenty-five bucks a piece!” Arthur looks at us and reaches into his pocket. He says, “What’re you complaining about? All I got for the gig is this,” and he pulls a five dollar bill out of his pocket. We thought he was bullshitting us. But he got to talking about it, and it seems that after paying the roadies, the manager, the promoter, and who knows what else, that’s all they got out of the gig. Five stinkin’ dollars! I’d heard other stories like that, and at this point it was becoming real to me that maybe Eightballs was way ahead of the game by doing our own business. But that wasn’t good enough for us. We had to sign up with a fuckin’ two-faced “manager.”

Eightballs had lasted as an entity for approximately two and a half years, from 1972 into 1974. The end came with the re-entry of Ken Schaffer into my orbit. Schaffer was a publicist who back in the late ‘60s had made a mess of re-wiring the Left Banke’s recording studio and lost one of their master recordings through incompetence. We’d been handling our own business affairs for two years and doing a fairly good job of it. But in the music biz, a band is supposed to have an agent and a manager and lawyer and all that shit in order to get a recording contract, a hit record, and a national tour. So they say; and of course, we wanted all that.

We had two “people” – I use the term loosely – pursuing us with the idea of becoming the manager of the Octet of Testicles, Steve Bass and Ken Schaffer. Bass was totally out of the picture, from my experience with him as manager of Benn Gunn; everyone agreed on that one, even Damian who I think saw it as some kind of conflict of interest for himself because of his other business dealings with Bass. But the guys were hungry for help, and they knew nothing of Schaffer like I did. I tried to tell them, but they outvoted me three to one and I ended up signing a paper with the rest of them. It was a disaster from the get-go. He altered our bad boy image which included a logo of little baby with a dog collar that said “SASS!” and began pasting some sort of Zen philosophy quotes on our promotional materials and writing up lies about us in our bios.

Next, he thinks he’s a record producer and wrangles us into accepting him behind the mixing board as a way of rewarding him for getting us the studio time. On one song, he mixed my guitar way down and mixed the maracas, which he played, way up high. I think he did it just to spite me; if not, he was just plain stupid, which is a fact anyway.

This is typical music business bullshit, it’s happened to the best and the worst of us. What really pissed me off is that I saw it coming and didn’t do anything about it before the shit hit the fan. The final outcome of all this was that I quit, which effectively destroyed the band. - TF

To see Tom play in the Los Angeles area check out his show schedule on his website, The Homemade JAM.

3 comments

I wonder if that was my old friend Damian Karch from Ft. Lauderdale in the 80’s?

Provided sound for Eightballs a couple of times and all I remember is lee singing “the flatter they are, the harder they ball, so I like the girls with no tits at all”

Thanks Tom for all your music and sharing your memories. You live on!!